Hélio Gracie

| Hélio Gracie | |

|---|---|

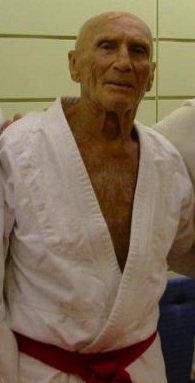

Hélio Gracie in 2004 | |

| Born | October 1, 1913 Belém, Brazil |

| Died | January 29, 2009 (aged 95) Petrópolis, Brazil Natural Causes |

| Other names | "Caxinguelê" ("Squirrel"),[1] "O Caçula" ("The Youngest")[2] |

| Style | Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Judo, Catch wrestling |

| Teacher(s) | Donato Pires Dos Reis, Carlos Gracie Orlando Americo da Silva Chugo Sato |

| Rank | 10th degree red belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu 6th degree red/white belt in Judo |

| Years active | 1932-1937, 1951-1955 |

| Other information | |

| Notable relatives | Gracie Family |

| Notable students | Rolls Gracie, Rickson Gracie, Royler Gracie, Royce Gracie, Relson Gracie, Rorion Gracie, Carlos "Caique" Elias |

Hélio Gracie (October 1, 1913 – January 29, 2009) was a Brazilian martial artist who together with his brothers Oswaldo, Gastao Jr, George and Carlos Gracie founded and developed the self-defense martial art system of Gracie jiu-jitsu, also known as Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ).[3]

Considered as the Godfather of BJJ, according to his son Rorion, Gracie is one of the first sports heroes in Brazilian history; he was named Man of the Year in 1997 by the American martial arts publication Black Belt magazine.[4] A patriarch of the Gracie family, multiple members of his family have gone on to have successful careers in combat sport competition including mixed martial arts (MMA).

Early life

[edit]Gracie was born on October 1, 1913, in Belém, Brazil. Contrary to popular belief, he was a talented athlete, and trained and competed in rowing and swimming since his childhood.[5] He had his first contact in martial arts at 16, when he started training judo (at that time commonly referred to as "Kano jiu-jitsu" or simply "jiu-jitsu"),[6] with his brothers Carlos and George. He also learned catch wrestling under the renowned Orlando Americo "Dudú" da Silva, who taught his brothers for a time.[7]

When he was 16 years old, he had the opportunity to teach a judo class, which helped him develop his family style, "Gracie jiu-jitsu".[8] When the director of the Bank of Brazil, Mario Brandt, arrived for a private class at the original Gracie Academy in Rio de Janeiro as scheduled Carlos Gracie, the instructor, was running late. Hélio offered to teach the class in Carlos's stead. When Carlos arrived with apologies, Brandt assured him it was no problem, and even requested that he be allowed to continue learning with Hélio.[citation needed]

Gracie realized, however, that even though he knew the techniques theoretically, the moves were much harder for him to execute. Consequently, he began adapting Mitsuyo Maeda's brand of judo, already heavily based around newaza ground fighting techniques. From these experiments, Gracie jiu-jitsu was created.[8] Like its parent style of judo, these techniques allowed smaller and weaker practitioners the capability to defend themselves and even defeat much larger opponents.[9][10] "Carlos and Helio Gracie ... brought a fresh eye to jujitsu just as their fellow countryman brought a special new approach to football."[11]

Aside from training with his brothers, Gracie learned further judo under Sumiyuki Kotani and Argentinian judo pioneer Chugo Sato.[12] He might have also got training under a practitioner named Hiraichi Tada.[2] However, the extent of his official training in this art remains unknown. According to Masahiko Kimura, Gracie held the rank of 6th dan in judo in 1951,[13] while according to Robert Hill, Kodokan records show Gracie at the rank of 3rd dan at the time, though Hill also noted that it was not unusual for Kodokan records to show a lower rank than that actually held by non-Japanese judo practitioners.[14][a]

Fighting career

[edit]First challenges

[edit]Gracie began his professional fighting career at 18 years old against boxer Antonio Portugal. The fight took place in the undercard of a "jiu-jitsu vs. boxing" event on January 16, 1932, which saw judoka Geo Omori defeating boxer Tavares Crespo. Gracie won his fight by submission in a short time,[15] probably an armlock in 40 seconds.[2] Portugal is sometimes incorrectly billed as a boxing champion.[16]

His second match would be the same year in a jiu-jitsu exhibition against Takashi Namiki in September. As Namiki had a 7 kg (15 lb) weight advantage and was a native of Japan just like the art of jiu-jitsu, he was expected to defeat Gracie. Namiki dominated the match, but Gracie wasn't defeated, leading it to a draw after several rounds.[15]

Matches against wrestlers

[edit]

Also in 1932, Gracie faced professional wrestler Fred Ebert on November 6. It was his biggest challenge up to the point, as Ebert outweighed him by 29 kg (64 lb) and was a decorated freestyle wrestler, and their match would have no time limit. Gracie was positive, claiming he would submit Ebert in a short time.[2] However, the bout lasted almost two hours, and was eventually stopped by the police at the promoters's discretion as none of the fighters was progressing or advancing position.[15] Again, this fight is sometimes registered as a vale tudo match,[2] but it was hosted under grappling only rules.[17] In an interview, Gracie claimed that he had to undergo an urgent operation the next day and that the stop was demanded by the doctor due to Gracie having a high fever caused by a swelling.[18]

In 1934, Gracie faced another jiu-jitsu practitioner named Miyaki. The latter (whose first name is unknown) was billed as a judo black belt, although he had fought only one professional fight, a loss against professional wrestler Robert Ruhmann.[16] He is usually identified as the famous judoka and catch wrestler Taro Miyake, a theory possibly initiated by Mark Hewitt in his book Catch Wrestling: A Wild and Wooly Look at the Early Days of Pro Wrestling in America (2005).[16] However, Miyake was 54 years old and weighted 90 kg (200 lb) at the time, while Miyaki's official stats were about 20 years old and 64 kg (141 lb), and photographic material seems to support them being different people.[16]

In any case, Gracie passed the first 20 minutes of the match in guard position before he climbed up to mount. He then applied a gi choke which Miyaki didn't surrender to, making the Japanese fall unconscious for the victory.[15]

On July 28, Gracie faced renowned professional wrestler Wladek Zbyszko who, very much like Ebert, had a 40 kg (88 lb) weight advantage (albeit was 22 years older) and was billed as a world champion. Although the match was promoted as a "catch-as-catch-can vs. jiu-jitsu" challenge, it was fought under jiu-jitsu rules, including judogis and a 20-minute time limit.[15] It was an uneventful affair; Gracie pulled guard at the opening and they spent the rest of the match in said position, ending in a draw. Still, it was seen as a moral victory for Gracie not to have been finished by the larger Wladek. The wrestler himself praised Gracie's courage and resistance.[15]

Gracie's next opponent was his own former teacher, Orlando Americo "Dudú" da Silva, who had defeated Hélio's brother George in a catch wrestling match earlier in the year 1935. Their match was stipulated as a vale tudo bout with a 20-minute time limit on February 2.[19] During the match, the two fighters exchanged punches before Dudú, heavier by 20 kg, took Gracie down. Gracie defended from the guard, but Dudú landed heavy punishment in form of ground and pound, breaking Gracie's nose with a headbutt and making him bleed profusely. However, the wrestler ended up spending all his energy in the assault, and it allowed Gracie to counterattack gradually with short punches from the bottom. When they returned to standing by the referee, Gracie landed two side kicks of the kind called pisão in capoeira, and the tired Dudú submitted verbally shortly after.[19]

Matches against judokas

[edit]After the fight against Dudú, Gracie was challenged by 5th dan judoka Yasuichi Ono to another vale tudo fight. This was met with heat by the Gracie side, as Ono had defeated George Gracie by choke in a jiu-jitsu match. Calling Ono a "cretin" in a newspaper interview, Gracie claimed to accept the challenge and the two were stipulated to fight in April 1935, but the bout was scrapped when Gracie pulled out.[19] Eventually, Gracie accepted to fight Ono, but only under jiu-jitsu rules, without points or judges and in December.[19] He also came to the match wearing a judogi with very short sleeves to make gripping difficult.[19]

The affair saw Ono, though lighter than Gracie by 4 kg (9 lb), executing an exact number of 32 judo throws on Gracie through the entire match, as well as almost finishing him with a juji-gatame in the first round. However, Gracie never gave up and escaped all his holds, including one in which he dived out of the ring to avoid a choke (a legal action at the time), and even had his own modest submission attempts in the form of an armlock and a gi choke near of the ending. After 20 minutes, the bout ended in a draw.[15][19]

On June 13, 1936, Gracie fought judoka Takeo Yano, a training partner of Ono who also had dominated George Gracie the previous year in a time draw. Again, Gracie demanded a match without judges and wore a modified judogi, and his brother Carlos predicted that Yano wouldn't last a single round. Indeed, Gracie showed improvement, threatening Yano with a gi choke in the second round, but Yano threw and took down Gracie repeatedly through the three rounds of the match, which ended in a draw.[15][19] Ono challenged Gracie for a future rematch after the bout, which Gracie accepted.[19] The same month, Gracie was involved in a challenge consistent in fighting three opponents the same night, being those Geroncio Barbosa, Manuel Fernandes and Simon Munich, but Gracie pulled out before the event and was replaced by his brother George.[15]

On September 12, Gracie faced a 2 kg heavier fighter named Massagoishi. He was billed as both a sumo wrestler and judo black belt, although Takeo Yano was quoted as skeptical of the second claim.[19] Gracie submitted Massagoishi with an armlock after 13 minutes of fighting. However, the match was criticized by the press, calling it "a comedy and a farce" due to Gracie and his opponent not living up to expectations.[15] The Brazilian Federation of Pugilism actually suspended Massagoishi for his inactivity during the bout.[15]

Gracie met Yasuichi Ono for the second time on October 3, 1936, again in a match under jiu-jitsu rules and with no points of judges. Press and critics were unanimous in Hélio's improvement from their first match, although Ono again threw Gracie a number of 27 times and controlled most of the match.[15][19] Around the time, Gracie had another rematch, it being against Orlando Americo da Silva and under grappling only rules. Gracie lost the match when he was disqualified for using a forbidden hold.[15][19] Gracie had also a match against Erwin Klausner in 1937. Klausner was mainly a boxer (although he was also known as a wrestler), but the match was contested under the usual jiu-jitsu rules. Gracie won by armlock at the second round.[15][19]

In 1937, Gracie retired from competition for the first time. He did not fight again until 1950. The year of his return, Gracie challenged famous boxing champion Joe Louis to a vale tudo match in one of his visits to Brazil, but Louis declined and proposed a boxing match, which Gracie rejected.[15][19]

Gracie vs. Kimura

[edit]In 1951, Gracie issued a challenge against a touring judoka and professional wrestler, Masahiko Kimura.[20] To fight him, Gracie faced before a lesser member of Kimura's troupe, Yukio Kato. Gracie and Kato went to a draw on September 6, 1951, with Kato immediately asking for a rematch. It took place on September 29, and it saw Gracie winning by choking out his opponent.[21] Although the win was controversial, the match against Kimura was realized, and it happened on October 22. Kimura defeated Gracie by gyaku-ude-garami at the second round in a convincing fashion. Gyaku-ude-garami then went on to be known as the Kimura lock.[22]

Academia Gracie vs Academia Fadda

[edit]Oswaldo Fadda represents a non-Gracie line of Brazilian jiu-jitsu. He was trained by Luiz França who was a student of Mitsuyo Maeda around the same time as Carlos and Hélio Gracie. Fadda was known for training the poor in Rio de Janeiro, and for the use of leg locks, which the Gracies considered low class. He trained a number of students and challenged Gracie's academy in 1953.[23] Fadda's academy won the majority of the matches.[24][25][26]

Gracie vs. Santana

[edit]In 1955, Gracie was challenged by Valdemar Santana, a former student of his academy who now trained and fought under the management of Carlos Renato and Haroldo Brito. Reasons why Santana left the Gracie team are diffuse; one of them is that he was expelled for taking a professional wrestling bout, something that their fighters had forbidden, while another tells how Santana accidentally flooded Gracie's gym while doing cleaning chores.[27] Gracie accepted the challenge of a vale tudo match, even though Santana was 16 years younger and 60 lb heavier.[27]

They fought in May, both wearing a jiu-jitsu gi. The bout lasted almost four hours,[28] possibly three hours and 40 minutes.[29] Gracie defended from his guard for most of the fight, hitting elbows to the head and heel kicks to the back, while his opponent threw punches through the guard. After a long time of fighting, Gracie got eventually tired, and Santana took over with headbutts and more strikes.[29] At the end, Santana lifted Gracie up and slammed him on the mat, and then landed a soccer kick to the head of a kneeling Gracie. Gracie was knocked out and his cornermen threw the towel.[27]

Although luta livre veteran Euclydes Hatem challenged Gracie after the fight, Gracie's bout with Santana was his final match before his retirement.[30]

Assault and Rufino Dos Santos

[edit]A dispute between Gracie's brother Carlos and Manoel Rufino dos Santos worsened after Dos Santos won a public bout against Carlos in August 1932. Subsequently, the conflict then moved to the newspapers, where Rufino criticized Carlos's skill and dismissed his jiu-jitsu credentials, leading Carlos, George and Hélio Gracie to assault him in front of his teaching place at the Tijuca Tênis Clube on October 18. They hit him repeatedly with a steel box and immobilized him for Carlos to apply an armlock, dislocating Rufino's shoulder so badly that it needed surgery.[2][5] The brothers were arrested and were convicted to two and a half in prison for assault, as well as for trying to run away during the arrest, but their connections to President of Brazil Getúlio Vargas granted them a pardon.[2]

Later life

[edit]Gracie's son, Rorion Gracie, was among the first Gracie family members to bring Gracie Jiu-Jitsu to the US. Royce Gracie, Rorion's younger brother, went on to become the first UFC champion in the organization's history; Helio coached Royce from outside the cage at UFC 1 and UFC 2.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]Gracie died on the morning of January 29, 2009, in his sleep in Itaipava, in the city of Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro.[31] The cause of death, reported by the family, was natural causes. He was 95 years old, and was teaching/training on the mat until 10 days before his death, when he became ill. [citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]Gracie had been married to Margarida for 50 years.[32] Because Margarida was unable to bear children, during their marriage, Gracie became the father of three sons (Rickson, Rorion, and Relson) with a nanny Isabel 'Belinha' Soares and four sons (Royler, Rolker, Royce, Robin), two daughters (Rerika and Ricci) with Vera.[33][34] After Margarida's death, he married Vera who was 32 years his junior.[32] Gracie was grandfather to many BJJ black belts, including Ryron, Rener, Ralek, Kron, and Rhalan.

In his late years, Gracie was quoted as saying: "I never loved any woman because love is a weakness, and I don't have weaknesses."[35]

Gracie was a member of the Brazilian movement Brazilian Integralism, which first appeared in Brazil in 1932.[36] Today, many members of the Gracie family are also close to the former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who received an honorary black belt from Robson Gracie in 2018,[37] although some family members were associated with the left under the Brazilian Dictatorship period.[38]

Documentary

[edit]On July 6, 2023, it was announced that ESPN Films is producing a documentary series on the Gracie family directed by Chris Fuller and produced by Greg O'Connor and Guy Ritchie.[39]

Awards and accolades

[edit]- Black Belt Magazine 1997 Man of the Year[40]

Fight record

[edit]| 19 matches | 9 wins | 2 losses |

| By knockout | 1 | 1 |

| By submission | 8 | 1 |

| Draws | 8 | |

| 9 wins (1 (T)KOs, 8 Submissions), 3 losses, 8 draws | ||||||

| Date | Result | Opponent | Location | Method | Time | Record |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 16, 1932 | Win | Submission (Armbar) | 0:40 | 1–0–0 | ||

| 1932 | Draw | 1–0–1 | ||||

| November 6, 1932 | Draw | 1:40:00 | 1–0–2 | |||

| July 28, 1934 | Draw | 30:00 | 1–0–3 | |||

| June 23, 1934 | Win | Submission (Choke) | 26:00 | 2–0–3[41] | ||

| February 2, 1935 | Win | TKO (Side kick to the spleen) | 3–0–3 | |||

| December 5, 1935 | Draw | 1:40:00 | 3–0–4 | |||

| 1936 | Draw | 3–0–5 | ||||

| 1936 | Win | Submission (Armbar) | 4–0–5 | |||

| 1936 | Draw | 4–0–6 | ||||

| 1937 | Win | Submission (Armbar) | 5–0–6 | |||

| 1937 | Win | Submission | 6-0–6 | |||

| 1950 | Win | Submission (Choke) | 7-0–6 | |||

| 1950 | Win | Submission (Choke) | 8–0–6 | |||

| 1951 | Draw | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | 8–0–7 | |||

| 1951 | Win | São Paulo, Brazil | Submission (Choke) | 9–0–7 | ||

| 1951 | Loss | Technical Submission (Kimura lock) | 9–1-7 | |||

| 1955 | Loss | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | TKO (soccer kick) | 3:42:00 | 9–2–7 | |

| 1967 | Win | Submission (Choke) | 10–2–7 | |||

| Legend: Win Loss Draw/No contest Exhibition Notes | ||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Gracie Academy – Hélio Gracie". Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reila Gracie (2013). Carlos Gracie: The Creator of a Fighting Dynasty. RG Art Publishing. ISBN 978-85-010807-5-2.

- ^ Ericson, E. Jr. (2009): Never Give Up: Helio Gracie Archived January 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Baltimore City Paper (December 30, 2009). Retrieved on April 6, 2010.

- ^ Jeffrey, Douglas (March 1999). "Helio Gracie on Brazilian Jujutsu". Black Belt. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ^ a b Roberto Pedreira, Choque: The Untold Story of Jiu-Jitsu in Brazil 1856–1949, 2014

- ^

H Irving Hancock (2009) [1905]. The Complete Kano Jiu-Jitsu – Jiudo – The Official Jiu-Jitsu Of The Japanese Government – With Additions By Hoshino And Tsutsumi And Chapters On The Serious ... Japanese Science Of The Restoration Of Life. Katsukuma Higashi. Grizzell Press. p. ix. ISBN 978-1-4446-5253-6.

the most modern and effective school of the art, the Kano system, which is to-day the real jiu-jitsu of Japan

- ^ "The history of Luta Livre and Vale Tudo in Brazil – Part I -". Luta Livre Academy.

- ^ a b "Gracie family patriarch Helio Gracie dead at 95". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on January 15, 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ "Helio Gracie, Promoter of Jiu-Jitsu, Dies at 95". New York Times. January 30, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ Gracie, Helio; Thomas De Soto (2006). Gracie Jiu-Jitsu: The Master Text (1st ed.). Los Angeles: Black Belt Communications. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-9759411-1-9.

- ^ Law, Mark (2007). The Pyjama Game: A Journey Into Judo (2008 ed.). London: Aurum Press Ltd. p. 222.

- ^ Roberto Pedreira (September 1, 2015). Choque: The Untold Story of Jiu-Jitsu in Brazil Volume 3, 1961–1999 (History of Jiu-Jitsu in Brazil 1856–1999). Joinville: Clube de Autores. ISBN 978-1507851142.

- ^ Kimura, M. (1985): My Judo (Part 2) Retrieved on April 6, 2010.

- ^ Hill, R. (2008): World of Martial Arts! Retrieved on April 6, 2010. (ISBN 978-0-5570-1663-1)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Roberto Pedreira (April 10, 2014). Choque: The Untold Story of Jiu-Jitsu in Brazil 1856–1949: Volume 1. Clube de Autores. ISBN 978-1491226360.

- ^ a b c d Roberto Pedreira (May 29, 2016). "Top 30 Myths and Misconceptions about Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu". Global Training Report. Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- ^ Roberto Pedreira (April 19, 2016). "Top 18 Myths and Misconceptions about Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu from Gracies in Action 1". Global Training Report. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "Kakutou Striking Spirit". May 1, 2002.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Marcial Serrano (September 11, 2010). O Livro Proibido do Jiu-Jítsu Vol. 2. Clube de Autores. ISBN 978-85-914075-2-1.

- ^ T.P. Grant (September 25, 2012). "Gods of War: Masahiko Kimura". Bloody Elbow. Archived from the original on October 6, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- ^ "Helio x Kato". YouTube.com.[dead YouTube link]

- ^ Chen, J. (c. 2003): Masahiko Kimura (1917–1993): The man who defeated Helio Gracie Retrieved on April 7, 2010.

- ^ "Academia Gracie vs Academia Fada: The actual results". - Bad ref to imgur.com. Please cite the newspaper properly. It appears to be DIARIO DA NOITE - Sexta-feira, 14 de Janeiro de 1955. Please verify.

- ^ "Non-Gracie Lineage: Oswaldo Fadda". August 16, 2014.

- ^ Reila Gracie, Criador de uma Dinastia - Carlos Gracie Sr., 2008

- ^ "Oswaldo Fadda | BJJ Heroes". July 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Waldemar Santana, The First Gracie Nightmare | MMAWeekly.com". February 8, 2015.

- ^ Grant, T.P. (January 2, 2012). "MMA Origins: Carlson Gracie Changes Jiu-Jitsu and Vale Tudo". Vox Media, Inc. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "Onzuka Brothers' Comprehensive History of Gracie Jiu-Jitsu". www.onzuka.com.

- ^ Marcial Serrano (June 15, 2016). O Livro Proibido do Jiu-Jítsu Vol. 6. Clube de Autores. ISBN 978-85-914075-8-3.

- ^ "Helio Gracie Dead". Sherdog.com. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ^ a b "Helio Gracie 2001 Playboy Interview". global-training-report.com.

- ^ "Gracie Family Tree". Gracie.com. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- ^ Knapp, Brian; TJ DeSantis (January 29, 2009). "Helio Gracie Dead". Sherdog.com. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- ^ "Vale Tudo Relics: The Life and Times of Helio Gracie". Sherdog.com. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ Rae, Steven (August 12, 2020). "Helio Gracie linked to 1930's Brazilian fascism movement". THE SCRAP. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ Kadirgamar, Simi (January 25, 2021). "He Trains Cops. His Jiu-Jitsu Family Has Deep Ties to the Far Right". The Daily Beast. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ Breathe Life Flow Rickson Gracie. ASIN 0063018950.

- ^ Otterson, Joe (July 6, 2023). "ESPN Films Sets Gracie Family Docuseries, Guy Ritchie Among Executive Producers (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ "Black Belt Magazine". blackbeltmag.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010.

- ^ Pedreira, Roberto Choque 1, Chap. 15

External links

[edit]- Academia Gracie de Jiu Jitsu

- Gastão and Hélio Gracie talk about Gracie Jiu-Jitsu – interviewed in 1997 for Gracie Jiu-Jitsu Videos

- Interview with Helio Gracie from Brazilian Playboy February 2001

- 1913 births

- 2009 deaths

- Sportspeople from Belém

- Brazilian male judoka

- Brazilian male mixed martial artists

- Mixed martial artists utilizing Brazilian jiu-jitsu

- Mixed martial artists utilizing catch wrestling

- Mixed martial artists utilizing judo

- Martial arts school founders

- Brazilian people of Scottish descent

- Gracie family

- People awarded a red belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu

- 20th-century philanthropists

- 20th-century Brazilian sportsmen